By Owei Lakemfa

Harry Belafonte did not seek social justice; social justice sought him out. When they met, he was ready for a life-long struggle to bring justice to the United States or more correctly, to bring the United States to justice even when he knew this might cost him his lucrative career, if not his life.

At first, he was contented writing cheques and funding the campaigns of the civil rights movement, but in 1964 he said Black Americans and a lot of the conscientious White Americans had gotten to the point they could no longer tolerate more lynching, beating of Black people and the ‘Whites-Only’ signs on public places.

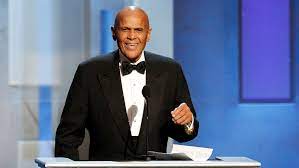

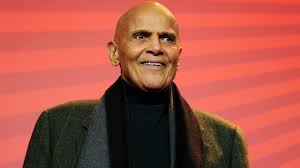

He had fame and fortune by the time he was 31 with his 1956 album ‘Calyso’ selling over a million records, the first long playing record by a single artist to hit that mark. But fame and fortune meant nothing to him; what did was to ensure the Black man, the Indian were treated in the US and elsewhere like a human being.

Reflecting on his life of struggles, he wrote in his 2011 memoirs My Song: A memoir of Art, Race and Defiance: “I was born into poverty, grew up in poverty, and for a long time poverty was all I thought I’d known.” When he started out, he had a role model: Paul Robeson, a famous actor, singer and activist. But Robeson had from the late 1940s been deliberately and openly destroyed by the US government. Employing state agencies like the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the American government had forced the entertainment agencies from hiring him. Realising that Robeson was a famous entertainer that could earn a living abroad, the US government seized his passport so he couldn’t travel outside the country. Belafonte said he learnt from this and was ever ready for a likely backlash from the government.

Another piece of injustice which galvanised him into battle was the crude attempt by the government to send the respected African American intellectual, Professor W.E.B. Du Bois, to prison. In 1950, Du Bois at 82, had ran for US Senate from the New York District on the ticket of the American Labour Party. Surprisingly, despite brazen racism and state campaigns against him, he had garnered some 200,000 votes. This led to a backlash by the state. Du Bois had gone on to call for the outlawing of atomic weapons. The US had in 1945 dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the establishment declared a campaign against atomic weapons as a USSR propaganda. It asked Du Bois and members of his Peace Information Centre to register under the 1940 Smith Act as “agents of a foreign principal”.

The Act criminalised any attempts to “advocate, abet, advice or teach“ the violent overthrow of the US government. Essentially, the government wanted them to sign admitting that they are spies. When Du Bois refused, he was put on trial. Belafonte said: “On the opening day of the trial, those of us who came to show our support were stunned to see the elderly Du Bois pulled roughly from a paddy wagon in handcuffs, ankle cuffs and chains like a prisoner on a southern chain gang.” The photographs of Du Bois arriving for trial, sent shock waves around the world and intellectuals like Albert Einstein protested. Unable to withstand the international pressures, America let Du Bois go.

In 1963, Du Bois at the age of 93 left US to join the Pan Africanist President of emergent Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah to build a new nation and new Africa. He changed citizenship and died two years later as a Ghanaian.

Belafonte continued the Du Bois anti-war activism, but where the latter had merely denounced the nuclear race, Belafonte developed the movement into a full one not just rejecting war but also taking a stand against the US fighting wars across the globe such as its illegal invasion of Iraq under dubious excuses.

Belanfonte’s leadership of the American anti-war movement was much more biting not just for its effectiveness, but also for the fact that while Du Bois had been an intellectual; Belafonte had been in the US Navy serving during the Second World War.

As part of his anti-war campaign, Belafonte on February 15, 2003 told a rally that President Bush was leading the US into a fraudulent war in Iraq as his predecessors had done in the conflicts in Vietnam, Grenada, Nicaragua, El Salvador and Cuba. He concluded by saying: “Dr. King once said that … if mankind does not put an end to war, war will put an end to mankind.” As it turned out, Belafonte was absolutely right about the senseless war in Iraq in which about one million died in the first five years.

Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans from August 23-31, 2005 killing 1,392 persons. The people felt abandoned by the American government, but when Venezuela offered massive aid, President Bush rejected it ostensibly because the country was socialist.

Belafonte went to Venezuela the following year to thank the Venezuelans for their gesture, and, standing beside President Hugo Chávez made one of his fieriest speeches: “No matter what the greatest tyrant in the world, the greatest terrorist in the world, George W. Bush, says, we’re here to tell you: Not hundreds, not thousands, but millions of the American people – millions – support your revolution, support your ideas, and, yes, expressing our solidarity with you.”

He was also angry with those he considered the Uncle Toms of the Bush team for pushing the war agenda and working “in the service of our (Black) oppression and those who create new ways in which to oppress us… And that is my argument with General Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice. I expect, as do others, that their history should have prepared them for a much better articulation about how to treat people globally.” Belafonte was a major funder of the Civil Rights and Student movements in the US and was quite close to Martin Luther King Jr.

So when King’s wife, Coretta Scott King, died in 2006, Belafonte was invited to speak at her funeral. However, when George W. Bush announced he was attending the funeral, Belafonte’s invitation was withdrawn. That, however, did not deter him.

He was a mentor to many across the world, including the famous Miriam Makeba. He was one of the best singers ever, churning out enchanting music and winning all the major awards available, including the Emmy, Grammy and Oscar.

But his life work was for social justice, and this was the least reported. Belafonte continued his fight for social justice until April 25, 2023 when our ancestors on the other side of the river, invited him to paddle over.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings