By Ifeanyi Igwebike Mbanefo

The lessons of history are universal and can be broadly applied across time, culture and races.

But its gems and information nuggets, often sitting layers below the main story, take some digging to find.

The challenge, oftentimes, is

arranging facts and data into meaningful order and assigning weights to them in a way that allows the cream to rise.

On NLNG’s 35th anniversary year, I consider it auspicious to share the lessons learnt from the history of the company and draw attention to indelible acts of the most important figures in the history of Nigeria’s most successful company.

Because of its special circumstances — it spent 35 years on the drawing board — and another 35 as a going business concern, the history of NLNG makes an interesting reading.

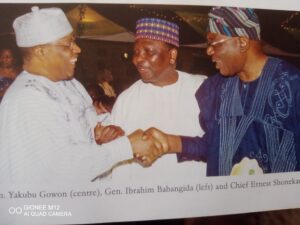

First on the list is former Head of State, Gen. Yakubu Gowon who conceived and nurtured the dream of building an LNG project in the years following the discovery of oil in commercial quantities.

He didn’t realize that dream, but he laid the foundation and provided a princely sum for the project in the National Rolling Plan before he was ousted from office.

It takes about seven years, from gestation to final investment decision, to build an LNG plant. As an army colonel, Muhammadu Buhari in his capacity as Petroleum Minister set up Bonny LNG project, the progenitor of NLNG.

The promoters of Bonny LNG Limited were NNPC (60%), Shell Gas B.V.(10%) British Petroleum (10 %), Philips Petroleum Worldwide Gas Limited (7.5%), Agip s.p.a (7.5%), and Elf Aquitaine du Gaz (5%).

BLNG shareholders agreement was signed in 1978 and the Federal Executive Council approved the award of a contract for preliminary engineering work on the gas gathering and transmission network to SNAM of Italy in 1979.

From 1975 to 31 October 1980, BLNG shareholders spent $18, 585, 700 developing the project and marketing the product globally.

The work progressed smoothly and the bid package for construction project was prepared and shared with the three consortia bidding for the contract. They were given till the end of March 1981 to submit their bids.

It was smooth sailing until January 1981, when Mr. Sam Akpe of NNPC submitted a 45 page memo to the Federal Executive Council seeking approval for Final Investment Decision on Bonny LNG Limited’s six- train project, potentially the biggest LNG project in the world.

Akpe told the president and ministers that the “total Federal Government equity contribution to the LNG project is not expected to exceed N1.3billion, and the projected foreign exchange earnings from the project in its 20-year life is expected to exceed $230 billion”.

Previous memos to FEC were in 1971, 1974, 1975 (2nd, 27th & 35th FEC meetings), 1976 and 1977.

It seemed an open and shut case, but against all expectations, the memo was not well received and as a result, Bonny LNG Limited was wound down in 1982.

Soon after, Vice President Alex Ekwueme, who had oversight responsibility for Petroleum Ministry began efforts to revive the project. NNPC was authorized to provide N5 million for economic, financial and legal consultants appointed to carry out independent feasibility study for an LNG project. The consultants were Arthur D Little (USA), Skoup & Co. (Ngr), First Boston Corporation (USA), International Merchant Bank (Ngr), Wilmer, Cutler and Pickering (USA), Sherman & Sterling (USA) and Lateef Adequate & Co (Ngr).

The army ousted Shagari and Ekwueme in December 1983 and Buhari on assumption of duties immediately restarted the LNG project.

Buhari’s choice of Mr. Gamaliel Onosode, a top notch corporate player and boardroom guru proved prescient. Onosode, first-class technocrat, administrator and Baptist Minister, was ambushed into becoming the team lead for LNG project by Buhari and his oil minister, Prof. Tam David West.

On the day of inauguration of the LNG Working Committee in March 1985, David West invited Onosode to his office and said: “Well I am sorry I didn’t tell you before, but I deliberately didn’t want you to know because I feared that you might turn down the request. We want you to be the chairman of LNG Working Committee.”

Onosode had protested that he was not the right person for the job, not being a technical man or an oil and gas man. But the minister didn’t budge.

At the inaugural meeting Onosode did something unusual. To everyone’s surprise, he proposed, without explaining why it was desirable, modification of the government’s terms of reference.

Years later, he explained why he took the action. “I was not happy with the logical sequence of the issues set out. We reorganized the the terms of reference so that we will not incorporate the company until we were satisfied that the project was viable.

Having reshuffled the cards, Onosode requested Shell, Agip and Elf to to state clearly the conditions under which they would go ahead with the project. Mr. B. A. Lavers, MD of Shell who spoke on behalf of foreign shareholders gave three conditions — market availability, execution of the shareholders agreement and an agreeable fiscal regime.

Despite stiff opposition from members of his team and Petroleum Ministry officials, Onosode reengineered the fiscal environment to make it conducive for LNG project. This is the origin of the NLNG Act, the superstructure on which NLNG rests today. Without Onosode’s intervention, NLNG would have remained a pipe dream.

President Ibrahim Babangida and his oil minister, Dr. Chu Okongwu, cancelled a final investment decision meeting on Tuesday 6 October 1992 to force the shareholders to drop the TEALARC process for the APCI which was widely popular in the industry. They also cancelled the contracting process which was mismanaged.

Asiodu who managed the petroleum ministry and LNG project in the 60s and 70s as permanent secretary returned to the ministry at a time of great uncertainty in 1993.

The Transition to had derailed, the economy in turmoil and the LNG project was gasping for air.

Buhari had in 1984 set up an escrow account for 20,000 barrels of crude oil daily to finance the LNG project, a tradition Babangida continued.

But on assumption of office in 1993 Asiodu, to his utmost surprise, found that there was not a kobo left in the kitty.

The problem of financing the project led Asiodu to recommend that the government sells five percent of the country’s 60 percent in the joint ventures with Agip, Philips and Shell to raise $500million which was deposited in an escrow account.

When Nigeria LNG Limited solicited his help in its lobby for Train 7, Chief Ernest Shonekan gladly accepted to intercede with the government, a task he championed it alongside Gen. Yakubu Gowon.

But before then, Shonekan had made vital contributions to the efforts to build LNG plant in Nigeria. As Head of the Interim Government Shonekan who served on the Board of Royal Dutch Shell was instrumental to reviving the project.

There’s enormous power in old school ties. Don Etiebet (Abacha’s Petroleum Minister), Godwin Omene and Brian Anderson, former Managing Director of Shell Nigeria attended Imperial College, London. At a private dinner, Etiebet and Omene enlisted Anderson’s help with major issues — more Nigerianisation of SPDC positions and revival of the LNG project.

Part of their private agenda was to make Omene, Deputy Managing Director (he later became the first indigenous DMD of Shell) and to resuscitate LNG project. They achieved these through deliberate planning and focused execution.

Former Head of State, Gen. Sani Abacha, was undeniably the hero of Nigeria’s LNG project, a project he started under very difficult circumstances. One might say that some of the problems — such as the killing of his friend Mr.Ken Saro-Wiwa — were self inflicted.

Yet, it is undeniable that Abacha and his advisers were an astute team. By the time Abacha came to power, the LNG project has recorded three near misses and has become a circus. To show seriousness, the shareholders agreement was amended to include a clause that any shareholder who withdraws from the project shall not only sell his investment for one dollar, but will also fulfil all its previous obligations.

This clause explained why Shell was unable to withdraw from the project despite wide global condemnation and picketing of its offices. Shell at the time of Saro-Wiwa’s death had invested $800million in NLNG.

Abacha also reduced Nigeria’s equity in NLNG to curtail the overbearing influence of government officials.

Gen. Abdulsalami Abubakar relied on the one dollar clause to force the hands of the shareholders to take the final investment decision on Train 3 in 1999.

His directive to the Board was to take the FID “on or before 15th February 1999, failing which before 27 February 1999 Presidential Elections”. ELF was uncomfortable with the economics of Train 3, and wanted to divest its shares. But it changed its mind when reminded of the one dollar clause.

Nigeria may have recorded more progress with Brass LNG project if the Jonathan regime adopted this strategy.

Theo Oelermans’ appointment was the watershed that changed the tide and fortunes of NLNG. A former Head of Shell Natural Gas Development for Africa during which he played a leading role in marketing LNG in the US and Europe. Appointed General Manager in Natural Gas in Shell Australia in 1982, he supervised the successful restructuring and development of the Northwest Shell LNG venture and marketing in Japan.

“Before I came to Lagos, I had talked to the shareholder, Shell, and said ‘are you really going to be serious about this project?’ And they showed me that they were absolutely serious.

Every project is different. Every project has its own problems. The main problem in Nigeria was the history of the project. It had been going on in some shape or form since 1963, which is a long time.

People did not always understand the problem which was caused by change of government. Other countries has similar problems. At a time in Australia, there was a government that wanted to keep all the gas in the country. Economically that was the wrong thing to do and that delayed the country’s LNG project.

I had set a number of specific targets for myself. One was to restore confidence of the buyers and to get them signed up properly. Second was to get the right sort of people employed, particularly the right sort of Nigerian staff. One set of people I was convinced that I really needed was the legal people and the top person, at the time, in my view, was Sena Anthony.

I went to see the Group Managing Director of NNPC and said that I would like to have Sena Anthony, please. And he said that I couldn’t have her; that she was important to him. I said ‘Sir, I’m going to come to your office every week to ask for her, so you can as well give her to me now. So I got her. Sena was one of the main contributors to the success of the project.

My feeling, looking back at all the projects I’ve been involved in, is that the most important success factor is not so much the customer or the shareholders, but the policy of government. The policies of government and consistent support of the government over the years are the most important success factors.

Fast forward to recent times and give Dr. Babs Omotowa his flowers. He restructured and save NLNG from ravages of world recession.

But more than anything else, Omotowa understood that LNG business is not just about liquefaction and shipment of molecules. He believed that a rising tide should lift all boats, insisting that the success of NLNG must rub off on all the stakeholders.

He built houses in Finima Community, awarded the Bonny-Bodo road that will link Bonny to Port Harcourt, built ultramodern laboratories in universities in the six geopolitical zones, built NLNG head office in Port Harcourt, commissioned Accenture to produce a master plan to make Bonny the Dubai of Africa and provided 25 year funding for the project.

He resisted the attempt of the Jonathan administration to plunge NLNG’s dividend into electioneering campaigns. Buhari later used the $2.1billion dividend as bailout to bankrupt states, unable to pay salaries when he assumed power in 2015. Omotowa later secured Buhari’s approval for T7 project.

The greatest sacrifice for the NLNG project was made by Finima Community. NNPC and Finima had reached an agreement that the community would be compensated for land on commercial rates.

But following the promulgation of the land use decree, the government and NNPC abandoned that agreement. The military administrator of Rivers State, Commander Suleiman Sa’idu revoked all rights of occupancy existing in respect of Finima Land.

The subsequent acquisition was published in the Rivers State Gazette no 198 vol. 11 of 22 November 1979. NNPC applied and obtained a Certificate of Occupancy from Rivers State Government for the parcel of land measuring 596.5 hectares in Finima. Of this land, NNPC set aside 514.63 hectares for exclusive use of NLNG — plant site, residential area and access road.

The title for the land was perfected by Governor Rufus Ada George on 30 April 1993. NNPC acquired an additional 64 hectares of virgin swamp some five kilometers south of Old Finima Town for resettlement of about 350 families displaced to build the plant.

Because NNPC used Finima Land as part of its equity, the foreign shareholders later insisted that the title for the land be issued in the name of NLNG.

Alhaji Abba Gana, the first deputy managing director of the company told the story:

On the day Saro-Wiwa was executed, NLNG and the banks participating on the escrow account signed an agreement. Everybody signed. The MD signed for NLNG. I was witnessing when the news broke that Saro-Wiwa had been executed. The shock in the room was palpable; representatives of Shell, Agip and Elf became apprehensive.

Two days later, President Nelson Mandela publicly called on Shell to pull out of Nigeria.

It was a serious request and Shell looked for a decent way to get out of the project. By then, we were about 10 days to two weeks away from taking the final investment decision.

One morning, I came into office and Oelermans was red-faced; very angry. I asked what the problem was and he said that the project was dead. Shell had indicated that the certificate of occupancy for the land on which the plant will be built was in the name of NNPC and therefore not acceptable.

I was shocked. I told Oelermans that I will try. So I left London that night and proceeded to Port Harcourt. I went straight to the governor’s office and had audience with him. I told him that Saro-Wiwa was executed in his state and the issue is trying to kill the LNG project.

After explaining the situation, he called the commissioner for lands and everyone involved and asked me to explain the situation to them. I did. And he directed that a new Certificate be issued before 10 am the next day.

I requested the governor to issue two certificates, one for the land belonging to NLNG and the other that belonging to NNPC.

The following day, I got the two certificates and I immediately faxed the NLNG certificate to Oelermans in London.

NLNG is Nigeria’s most successful company. It invested $2.5 billion and has reaped over $40 billion in dividends, $19 billion in Foreign Direct Investment, $32 billion from sale of feed gas, over 20,000 direct and indirect jobs, and 4 percent in GDP. And billions of dollars in taxes.

It seems, however, ironic that the Finima, its sacrificial host community has been left behind.

After 35 years of operation, the community still remains a ghetto, completely unaffected by the wealth, power and modernity of NLNG, Shell and ExxonMobil, three of its most prominent tenants.

Some lawyers believe Finima deserves compensation for its land from NLNG. Others said that the fraction of NNPC’s equity attributable to Finima land should rightfully and beneficially belong to the community, with all privileges and benefits accruable.

The status of NLNG, a private company, that is accorded the privileges of a public company presents everyone with a legal and moral dilemma.

But no one is confused about the poverty and neglect of this host of all the big oil majors. The plight of Finima people is a crying shame. It has suffered for 70 unmitigated years for its unrequited love to Nigeria and NLNG.

— Ifeanyi Igwebike Mbanefo, former spokesman for NLNG, is the author of a widely acclaimed book, The Story of Nigeria LNG Limited. He currently lives in Canada.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings