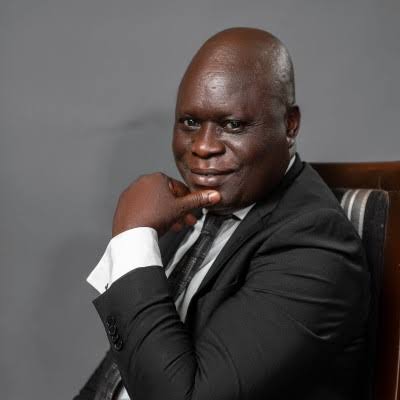

By Bankole Ebisemiju

Working with The Guardian was educative and rewarding. Though it comes with its challenges, seeing your by-line in the newspaper compensate for the rigorous efforts and dangers of sourcing and writing a news reports or feature articles.

I joined the newspaper in 1991 and handled the MediaWatch (later renamed Media) till 2005. The situation was smooth. Covering the Journalism, Advertising, Public Relations and Broadcasting sectors of the media was a fulfilling experience.

However, the situation change drastically when Major General Ibrahim Babangida decided to manipulate the transition to civil rule programme. Covering media activities, issues and developments took a dangerous dimension.

The onslaught on the media was tense and as a media reporter/correspondent, one has to be on top of the game, as these onslaughts must first be reported with follow-up reports on development on case by case basis. IBB tenure witnessed several closures cum arrest and detention of journalists. But General Sani Abacha’s period from 1993 to 1998 when he died takes the trophy as he unleashed venom on the media as he prepared to transmute into a civilian president. Continuing a pattern of incessant government attacks on the press, thousands of copies of newspapers were seized in 1997, and news vendors, as well as journalists, were thrown in jail for publishing or selling news that offended the government. Leading editors continue to serve long prison terms on trumped-up charges or are detained without trial under executive decree.

This aggressive government crackdown on the media forced editors to operate underground clandestinely as “guerrilla journalists” and frequently changing the location of newsrooms and printers to evade capture.

Apart from the attacks on the media, the government commenced implementation of new press laws severely restricting the media. A provision in the 1995 draft constitution – upon which the promised transition to civilian rule in 1998 will be based – proposed a National Mass Media Commission, which will regulate the existence of radio, television, newspapers, magazines, and publications generally, as well as restrict newspaper circulation to their provinces and interfere in the daily affairs of already existing media organizations.

The Newspaper Registration Decree 43, issued in 1993, finally went into effect. The decree requires a non-refundable annual application fee of N100,000 (US$1,250), a pre-registration deposit of N250,000 (US$3,100), and allows the government to arbitrarily assert control over which newspapers receive licenses.

The Guardian all along was committed to holding government accountable, thus the attacks required me to be on top of my game. Each arrest were reported and followed up with visits to family members of those arrested and detained as well as generating stories to put the dangerous situation in front-burner of public discussion. Several times I was “commanded” to confirm from the State Security Service whether the journalists were with them. I was able to do my best. I remembered a Nigerian Guild of Editors Conference which I covered at the Airport Hotel. Chief Tom Ikimi, the Minister of Foreign Affairs was billed to address the gathering. He did not arrive until after I had left the venue to file my story. Of course, his speech was on the cover pages of major newspapers except The Guardian. I received my second query for missing a story. My first query was when I judged an interview with the Registrar of the Nigeria Institute of Journalism more important than that of the gathering of top editors. I was slammed with a query and suspension without pay.

This notwithstanding the beat goes on as coverage of the Abacha media onslaught became more intense. Niran Malaolu, editor-in-chief of the independent newspaper “The Diet” was charged with “treason.” The journalist was accused on 14 February 1998, by a special military court based in the northern town of Jos, of plotting to overthrow General Sani Abacha on 21 December 1997. Malaolu was liable to the death penalty if he is found guilty. I kept vigil at his house in Ogba, Ikeja reporting developments. Same for four Nigerian journalists sentenced to 15 years in jail by a special military court sitting behind closed doors. They were convicted of “concealing information and involvement to varying degrees in the failed coup d’état” of 1 March 1995. They are Kunle Ajibade, editor of the magazine The News, Ben Charles Obi, editor of the magazine Weekend Classique, George Mbah, a journalist with the independent weekly Tell, and Chris Anyanwu, editor of The Sunday Magazine.

I remembered how I discovered and reported the fake editions of Tempo and The News published by agents of the military junta. On 15 August 1994, The Guardian group of publications was closed by the junta. The closure was in connection with The Guardian on Sunday publication of 14 August 1994 front page lead story titled Inside Aso Rock which attempted to provide insight into the decision-making mechanism at the nation’s seat of power in Abuja. The Federal Government explained that the closure was prompted by the need to protect national security. Very convenient excuse but not the truth! This development threw journalists from The Guardian into panic mode. The management too adopted the strategy of shortlisting some staff on stand by operations while the struggle for the reopening goes on in the court. Though I was one of those shortlisted, the arrangement could not make life easy.

I had to map out my own survival strategy.

I approached the then Deputy Managing Director of a top advertising agency to solicit a temporary appointment in one of their subsidiaries. He gave me a note to the management of their public relations arm and I started work. I worked with the team on some briefs. This gave me an opportunity for practical experience practicing public relations. The pay was not much but manageable. I go to the office and assignments with my jalopy Volkswagen beetle. It was during this period that the engine knocked due to my inability to buy engine oil. It knocked at Ogba on my way home. I had with me N100!

I was head hunted for the Third Eye newspaper in Ibadan to man the Arts and Media desk. I’ll source my stories in Lagos and travel to Ibadan, work on the pages overnight and return to Lagos the second day. It was a gruesome venture but man must survive.

I had to think outside the box. The Third Eye experience affected me psychologically and physically. I threw in the towel.

Through creative thinking I conceptualized a talent hunt for pupils and students in primary and secondary schools to develop their creative potential. We got the National Gallery of Art under the leadership of the late Dr. Paul Chike Dike as main partner and Cadbury Nigeria through its Bournvita brand as major sponsor. We ran the talent hunt with the NGA for ten years before pulling out. It is still a yearly programme organized by the NGA.

It was good to return to The Guardian when it was reopened. The closure took something away from me-the passion for journalism! I finally left to a new found love in the Social Development sector, as a Development Communication Specialist and worked with international organizations to horn my skills.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings